Fundamentals of Algebra

This is a guide on the fundamentals of Algebra.

Table of Contents

- Algebra and Number Sets

- Understanding Functions In Algebra

- Linear Functions In Algebra

- Solving Linear Equations

- Inequalities of the Linear Kind

- Piecewise Functions

- Solving Quadratic Equations

- Factoring Quadratics

- Algebraic Functions

- Transforming Graphs

- Nonlinear Functions

- Why We Factor Polynomials

- Fundamental Theorem Of Algebra

- Solving Inequalities

- Power Functions and Exponents

- Composition of Functions

- Inverse Functions

- Exponential Functions

- Logarithmic Functions

- Properties of Logarithms

- Logarithmic Equations

- Equations With Two Variables

- Systems of Equations in Two Variables

- Linear Equation With Three Variables

- Linear Systems with Matrices

- Properties of Matrices

- Inverses of Matrices

- Determinants

- Parabola Equations

- Ellipses

- Hyperbolas

- Sequences

Algebra and Number Sets

I have been wanting to start this series for a long time. I think advanced Algebra is very interesting and I want to explore it as much as I can. However, I need to start out with the basics for those that would not be familiar with it.

I have been thinking how far in the beginning I wanted to start. It eventually occurred to me that I wanted to start at the very beginning for the sake of my son. My son is young and has no interest in math yet. I hope that changes soon.

This series is supposed to be something that he can eventually follow and learn from if he develops that interest. I will just expose math to him regularly and hope for the best.

Number Patterns

The basics of numbers is about patterns. Whenever we look at a series of numbers a pattern often develops. As we go about our day to day activities we use numbers and the resulting patterns to help us do a better job.

Most of the time we do this unconsciously. However, if we think about it a little more we can use this number behavior to our advantage.

First, let us look at numbers from a very basic standpoint so we are all on the same page. Numbers can be rational, irrational, natural or integers.

5 = natural, integer, and rational

-1.2 = rational

13/7 = rational

sqrt -7 = irrational

-12 = integer and rational

sqrt 16 = natural, integer, and rational because it evaluates to 4.

These definitions will help us later on when dealing with certain mathematical situations. Each type of number I have listed above has certain rules about what can be done with them. It is these rules that dictate how we interact with problems to solve them. From here on I will give some basic examples of these points to cement them in your heads.

Example 1

If you have 72 computers with varying numbers on 3 different pallets, how many computers are on each pallet on average?

This is a nice and easy example to start with. Most of you can instantly recognize that the answer is 24. A few might have to bust out a calculator but you understand how to solve the problem at the very least.

Now lets do another example that many adults don’t know how to do but is simple nonetheless. This one is about calculating percent change in two numbers. I asked a couple people and neither adult knew how to do this off top of their heads.

They are both proficient with Excel though. Kind of concerning isn’t it? I think we often rely on our tools too much. In fact, many people can’t do things by hand anymore.

That is also the reason why I get asked to help with these things, as these people don’t know why the calculations they do work or don’t work.

When something does not give the expected results, they can’t debug their own problem to figure out why.

Example 2

Solve: Calculate the percent change in these two numbers: 38 and 57

I will explain what we are doing so it is clear. First, we get the difference between the two numbers. 57-38 = 19. We then divide the difference by the lesser number. 19/38 = .5. Multiply the .5 times 100 and that is your percent change. .5 * 100 = 50% change.

If you notice, I am going over some common tasks that everyone should know how to do. I am trying to explain how they work also. Another problem someone might be curious about is how fast the Earth moves. So lets work on this.

Example 3

Solve: Calculate the speed of Earth in its orbit

Let’s think about what we know. Its orbit is the elliptical path it takes around the Sun. An elliptical path is a very stretched out circle in simple terms. The Earth goes around the Sun because of the Sun’s gravitational pull. We also know that the average radius of our orbital path is 93 million miles. The Earth also takes approximately 1 year to travel this path. We will use this simple geometry to figure out the rest of what we need.

Speed is distance divided by time. Our first task is to find out how far we travel in a year. How many miles is it really? We want to use the formula for a circle here because it’s a fair approximation. The distance around a circle is 2* pi * r.

D = 2 * 3.14 * 93,000,000 which is rounded to 584,000,000 miles. Hours in a year = 365 * 24 = 8760.

We have our problem data now so just divide. 584,000,000 / 8760 = 67,000 miles per hour. I rounded that up. That is how fast we are traveling around the Sun.

Another good ability to have is to be able to calculate the volume of common objects. This is handy in cooking, 3d printing, and estimating the mass of stellar objects 50 billion light years away. Fun right! So what would the volume be of a simple soda can?

Example 4

Solve: Find the volume of the infamous soda can

This soft drink is a cylinder. That is its shape. The formula for the volume of a cylinder is v = pi * r^2 * h. V = volume, pi = 3.14, r = radius, and h = height. If r = 1.4 inches and and h = 5 inches, use these figures to find the volume.

V = (3.14) * (1.4)^2 * (5).

V = 30.78 cubic inches.

Another good tool to have in your mental repertoire is being able to measure the thickness of objects through basic calculations. It’s actually a pretty quick calculation once you understand it. Lets try it out.

Example 5

Solve: What is the thickness of an object that is 15 cm by 35 cm and weighs 5.4 grams

Thickness = volume / area. 1 cubic cm of this material weighs 2.7 grams. We start by finding the volume. Volume in this case will be length * width * thickness.

We know the material weighs a total of 5.4 grams and also that 1 cubic cm is equal to 2.7 grams. So that means we have 2 cubic cm of material, which is our volume.

The area of this material is easy since it seems to be rectangular. 15 cm * 35 cm = 525 cm ^2.

Thickness = volume / area. Thickness = 2 cm ^3 / 525 cm ^2. Thickness = .0038 cm. That is our answer. Its pretty thin isn’t it? This process does show you how useful it is to be able to do these calculations. You have to have the correct information up front of course.

Conclusion

I am going to stop here for this entry. In this topic I talked about the types of numbers we often see. I hopefully explained why it is important to do calculations by hand at first, until they are understood.

We did several examples together and I hope they were able to be understood by my explanations. This will be an ongoing series and I think it will be a lot of fun to learn and teach others. Percy, if you read this far, this one was for you my son!

Understanding Functions In Algebra

Functions are a type of relation that tie numbers together. They have to have a mutual meaning, but when they do, the data given can be very meaningful. Beginning functions often use tables for a visual aid. Tables in this fashion show the direct relationship between a set of numbers.

Notation and Pairs

When talking about functions, the notation y = f(x) is traditionally used. This means that when (x) is used as an input into (f), then the result is y. That is a fundamental relationship and must be understood. It is important to realize that a function returns a set of ordered pairs, like (x,y). A relation that has one output for each input is, by definition, a function. (x) is the independent variable and (y) is the dependent variable.

A set of inputs (x) is called the domain of the function. The set of related outputs (y) is the range of the function. A letter (f) is usually the name of a function. A function can be represented in words, a table, or a diagram. They all mean the same thing. Each method will have its limitations.

Functions can be represented verbally, graphically, symbolically, or numerically. There is no best way, it depends on the situation and the data you want to show.

Every function is a relation but not every relation is a function. This is important to remember. The domain is the set of all read numbers for which it is defined.

Constant Functions

I want to add some detail to our definition of functions. They can be considered in another light, that is, they can be linear or nonlinear. An example of a linear function is called a constant function. It should not be too hard to surmise what this is. A constant function is one who’s output remains constant. These are actually very common.

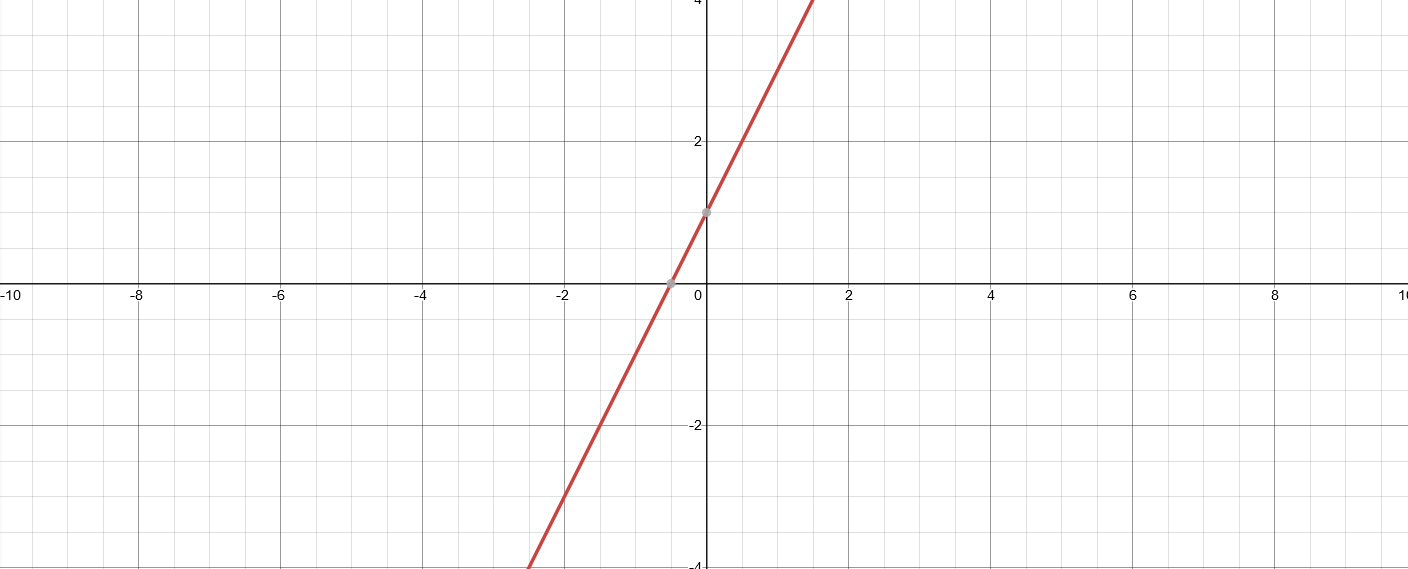

Linear Functions

This is a type of function where the output has the same rate of increasing or decreasing. It is represented by f(x) = ax + b. If a=0 at any point then we will just have a constant function. So in a linear function, each time x increases, f(x) changes by the amount of a.

Slope

The graph of a linear function is a straight line. Slope is the number that indicates the inclination of this line. If you have two points, slope = m = \(\frac{\delta y}{\delta x}\). If this slope is positive, it rises from left to the right. However, if its negative, the line sinks from left to right.

Example 1

Find the slope of the line passing through the points (-2,3) and (1, -2).

You calculate it like this:

\( m = \frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1} = \frac{-2-3}{1-(-2)} = \boxed{\frac{-5}{3}} \)

Slope like this is also known as rate of change of a function. It is also a constant function.

When using a graph to figure out estimates, the units will be easy and given for you. It will be the units for the y-axis over the x-axis. Take advantage of this.

Nonlinear Functions

Nonlinear functions are easy to explain. They are functions with variable output. So the output does not increase or decrease with any regular interval. If you were looking at a graph, the line would be curved. This is what a curved line means.

If you are looking at a table of data and wonder if it is linear or nonlinear, just examine the output. That part should be labeled clearly. The output will have the same rate of change if it is linear, otherwise it is nonlinear.

Average Rate of Change

Since the graphs of nonlinear functions are not straight, there is no single slope. Instead, there are many different slopes in a particular curve. However, we can take an average of the slopes to get a general idea. This is an important calculus topic too. If we have two points on a curve and draw a straight line connecting them, we call this a secant line. So the average rate of change is telling us, on average, how fast a quantity is changing. the average rate of change is just the slope of that particular line between two points.

When a function is constant, its average rate of change, or slope, is 0. In a linear function such as:

\( f(x) = ax + b \)

its average rate of change is equal to a, the slope of its graph. A nonlinear function has a variable rate of change.

Difference Quotient

The difference quotient is encountered a lot in calculus. It looks like this:

\( \frac{f(x + h) - f(x)}{h} \)

Example 2

Calculating A Difference Quotient

If \( f(x) = x^2 - 2x \) Find f(x+h)

Our expression is \( x^2 - 2x \) . We substitute \((x+h)\) for every (x) in our expression.

\( f(x + h) = (x + h)^2 - 2(x + h) \)

Now multiple the expression out.

\( f(x + h) = x^2 + 2xh + h^2 -2x -2h \)

Ok that gives us \( f(x + h) \) . Now we input that into our difference quotient.

\( \frac{ f(x + h) - f(x)}{h } = \frac{ x^2 + 2xh + h^2 -2x -2h- (x^2 - 2x) } {h} \)

Lets rewrite that ending part so everything has the correct sign.

\( \frac{ f(x + h) - f(x) } {h} = \frac{ x^2 + 2xh + h^2 -2x -2h -x^2 + 2x } {h} \)

It should be immediately obvious that a few things will cancel out. Lets do that.

\( \frac{ 2xh + h^2 -2h }{h} \)

\( \frac{ h(2x + h -2) } {h} \)

\( \boxed{2x + h -2} \)

This is our answer. These problems are usually designed so they cancel out certain values to make it work. So when working these, if the problem does not behave like that, you might have made a mistake and need to go back and look at it.

Example 3

The distance in feet that a racehorse travels is given by the function

\( d(t) = 2t^2 \)

Find \(d(t + h)\).

Find the difference quotient.

We will be substituting \((t+h)\) for t in the expression \(2t ^2\).

\( d(t+h) = 2(t+h)^2 \)

\( 2(t^2 +2th + h^2) \)

This gives us \((2(t+h)\).

\( = 2t^2 + 4th + 2h^2 \)

Now lets calculate the difference quotient.

\( \frac{d(t+h) - d(t)}{h} = \frac{2t^2 + 4th + 2h^2 -2t^2}{h} \)

Cancel stuff out and rewrite it.

\( \frac{4th + 2h^2}{h} = \frac{h(4t + 2h)}{h} \)

Cancel those h’s. We get:

\( 4t + 2h \)

If t=7 and h=.01, then the difference quotient becomes:

\( 4t + 2h = 4(7) + 2(.1) = \boxed{28.2} \)

The slope on a graph is the degree of the rise and fall of a line between two points. This is also the rate of change. Rate of change tells us how fast any quantity changes. This then leads us to difference quotients.

Conclusion

So functions are very interesting. They can tell us a nice picture on what each one means. Constant and linear functions are easy to understand but its also important to remember what they represent and how they look graphically.

Linear Functions In Algebra

A function or mathematical model will not ever be exact. So a linear function is really just an approximation. With that said, linear functions and models of data can be very useful. You see them often in graphs. They are the straight lines you see representing data. A linear function usually takes the form \(f(x) = ax + b \). A line from this function on a graph can intersect one or both of the axes. Lines like this can have a slope. Slope is shown as :

\( \frac{\Delta y}{\Delta x} \).

If the line crosses the y-axis it is called the intercept. If we have a linear function \(f(x) = 2x + 5 \), 2 is the slope and 5 is the y-intercept.

The x-intercept is where the line crosses the x-axis. If we fill out the equation with intercepts and slope it should equal out to zero. This is how you can check your answer. The x-intercept is also called the <zero> of the function. If the slope of a function is not zero, then the graph only has one x-intercept.

Modeling Functions

Functions are often used to model data. When we have a graph of data, the slope also tells us its rate of change. This is useful if it is changing at a constant rate. The constant rate of change is the slope of a straight line on a graph. So basically, if the slope is the same between two points then you can use a linear function. An exact model will be able to describe the data very closely, if not exactly. We usually never see exact models of anything outside of a textbook so keep that in mind.

Linear Regression

The example I have mentioned have all been regression problems. This is because we have used one variable to predict the value of another variable. This is the very definition of linear regression.

Equation Of A Line

As discussed before, any quantity that increases at a constant rate, can be modeled with a straight line. The slope of this line can be computed easily. The \( \Delta y = y - y_1 \) and \(\Delta x = x - x_1 \) are what is needed. In fact:

\( \frac{ \Delta y}{ \Delta x} \) will give us the slope itself. This is the slope formula. It also has other versions.

They look like this:

\( m = \frac{ y - y_1}{x - x_1} \)

and

\( y = m(x - x_1) + y_1 \)

Point-Slope Form

You will use the last two equations more than the first. The first is just a generalization. The latter two are just different forms but say the same thing. The last one is also known as the point-slope equation. So here is an example I found to show how this works.

Example 1

Find an equation of the line passing through the points (-2, -3) and (1,3).

You will start by finding the slope or rate of change. If you are looking at a graph, this will be the line you are looking at.

\( m = \frac{3 - (-3)}{1 - (-2)} = \frac{6}{3} = 2 \)

That gives us a slope of 2 for this line. The line consists of the two points mentioned above. Now we just use one of the points along with our slope and put it in the point-slope form. I will use the first point given.

\( \boxed{y = 2(x + 2) - 3} \)

Slope-Intercept Form

The slope-intercept form is another variation. It is \( y = mx + b \). M is the slope and b is the y-intercept.

Example 2

Find a point-slope form for the line.

First we have a slope of \(-\frac{1}{2}\) passing through the point (-3, -7).

The point-slope form is \( y = m(x - x_1) + y_1 \). Just plug in the values that we were given. We get:

\[(y = -\frac{1}{2}(x +3) -7 \)

We get the slope-intercept form by just simplifying this expression.

\( y = -\frac{1}{2}x - \frac{3}{2} -7 \)

\( \boxed{y = -\frac{1}{2}x - \frac{17}{2}} \)

Intercepts

An equation of a line has another form which is called the standard form. It looks like: \( ax + by = c \). This is the third equation of a line we have talked about now. So we have in total: point-slope form, slope-intercept form, and now the standard form. To find the intercepts from a standard form equation, you will set y or x to zero and solve the equation. If y is set to zero then you will get the x intercept. Setting x to zero will then give you the y intercept.

Example 3

Find the intercepts for the equation \( 4x + 3y =6 \).

Start with setting y=0.

\( 4x + 0 = 6 \)

\( x = 6/4 \)

\( x = 3/2 \) = x-intercept

Now let us set x to zero to find the y intercept.

\( 0 + 3y = 6 \)

\( y = 6/3 \)

\( \boxed{y = 2} \) = y-intercept

Other Types Of Lines

There are even more types of lines you can see on a graph. Don’t worry, they are all easy. The first is a horizontal line. On a graph, this represents a constant function. It is the easiest to recognize and do anything with. A horizontal line has the same y coordinate but different x coordinates. It also has a zero slope.

A vertical line is the opposite. It will have the same x coordinate but different y coordinates. Its slope will be undefined.

Parallel lines are the next type. They can’t be vertical to be considered parallel. These lines also need to have the exact same slope. If these conditions are met they will be considered parallel.

Perpendicular lines are the last type. For two lines to be perpendicular they need to be negative reciprocals.

Related Data

This may seem like common sense, but it is also important to state. Data can be related to each other. If one quantity changes then another will change because it can be directly related. However, it is important to be able to see if data changes because it is related or not.

Recapping It All

Point-slope form = \( y = m(x - x_1) + y_1 \). This is used to find the equation of a line if you have two points or one point and a slope to work with.

Slope-intercept form = \( y = mx + b \). This is a discrete equation for any certain line. It is obtained by using the slope and and the y-intercept.

Interpolation = Estimated values that are between two data points.

Extrapolation = Estimated values that are not between two data points.

Conclusion

In this section I covered more of the basics, which include line equations and working with data points. The next chapter will be over linear equations and working with them.

Solving Linear Equations

One of the goals in mathematics is solving equations. The most fundamental of these is linear equations. In this chapter, I discuss how to solve them.

Introduction

An equation is a statement that says two mathematical expressions are equal. Equations can have one or multiple variables. Solving an equation means finding all values for the variable that make the equation a true statement. The simplest type is the linear equation. A linear equation with one variable is an equation that can be written in the form: \( ax + b = 0 \).

Example 1

Solve the equation \( 3(x-4) = 2x - 1 \).

\( 3x - 12 = 2x - 1 \)

\( \boxed{x = 11} \)

Example 2

Solve \( 3(2x - 5) = 10 - (x + 5) \).

\( 6x -15 = 10 -x -5 \)

\( 6x - 15 = 5 - x \)

\( 7x = 20 \)

\( \boxed{x = \frac{20}{7}} \)

When fractions or decimals are in an equation, you multiply each side of the equation by the least common denominator of all fractions in the equation.

Example 3

Solve: \( \frac{T-2}{4} - \frac{T}{3} = 5 - \frac{1}{12}(3 - T) \)

\( 3(T-2) - 40T = 60 - (3 - T) \)

\( 3T - 6 - 4T = 60 - 3 + T \)

\(-2T = 63 \)

\( \boxed{T = \frac{-63}{2}} \)

Example 4

Solve: \( .03(z - 3) - .5(2z + 1) = .23 \)

To eliminate decimals in this case, multiple them by 100.

\( 3(z-3) - 50(2z+1) = 23 \)

\( 3z - 9 - 100z - 50 = 23 \)

\( -97z = 82 \)

\( \boxed{z = \frac{-82}{97}} \)

The equation \(f(x)\) = \(g(x)\) results whenever the formulas for two functions (f) and (g) are set equal to each other. A solution to this equation corresponds to the x-coordinate of a point where the graph of (f) and (g) intersect.

Example 5

Solve: \( 2x - 1 = \frac{1x}{2} + 2 \)

\( 2x = \frac{1}{2} x + 3 \)

\( \frac{3}{2}x = 3 \)

\( \boxed{x = 2} \)

Linear equations and functions can be solved symbolically, graphically, and numerically. Symbolic solutions are always exact. Graphical and numerical solutions are approximated to some degree. The intermediate value property states that if two points are connected, then (f) assumes every value between the (y) points at least once.

Example 6

A survey found that 76% of bicycle riders do not wear helmets. Find a symbolic representation for a function that computes the number of people who do not wear helmets. Also, there are around 38.7 million riders who do not wear helmets. Write a linear equation that gives the total number of riders.

A linear function that computes 76% of (f) is: \( f(x) = .76x \).

We must find the x-value for which \( f(x) = 38.7 \). The equation is \( .76x = 38.7 \) which evaluates to \( \boxed{x = \frac{38.7}{.76}} \) and is equal to 50.9 million riders.

Solving Problems

Read the problem and make sure you understand it. Assign a variable to what you are being asked to find. Write an equation that relates the quantities described in the problem. Solve the equation and determine the solution. Check your solution and make sure it seems plausible.

Example 7

A large pump can empty a tank of gasoline in 5 hours and a smaller pump can empty the same tank in 9 hours. If both pumps are used to empty the tank, how long will it take?

We are looking for time, so let time equal (T). In one hour the large pump will empty \(\frac{1}{5}\) of the tank and the smaller pump will empty \(\frac{1}{9}\) of the tank. The fraction of the tank they will empty together in 1 hour is \( \frac{1}{5} + \frac{1}{9} \). So, in (T) hours, the fraction of the tank that the two pumps can empty is \(\frac{T}{5} + \frac{T}{9} \). Since the tank is empty when this function reaches 1, we can use \(\frac{T}{5} + \frac{T}{9} = 1 \).

\( \frac{T}{5} + \frac{T}{9} = 1 \)

\( \frac{45T}{5} + \frac{45T}{9} = 45 \)

\( 9T + 5T = 45 \)

\( 14T = 45 \)

\( T = \frac{45}{14} \)

\( \boxed{T = 3.21 hours} \)

Example 8

In one hour an athlete travels 10.1 miles by running 8 mph and then at 11 mph. How long did the athlete run at each speed?

We are asked to find the time spent running at each rate. If we let (x) represent the time spent running at 8 mph, then 1-x represents the time running at 11 mph because the total running time was 1 hour.

Distance (d) equals rate times time (T) or \( d=rt\). In this example, we have two rates and two times. The total distance must sum to 10.1 miles.

\( d = 10.1 = 8x + 11(1-x) \)

\( 10.1 = 8x + 11 -11x \)

\( 10.1 = 11-3x \)

\( 3x = .9 \)

\( \boxed{x = .3} \)

So the athlete runs .3 of an hour at 8 mph and .7 of an hour at 11 mph.

Example 9

A person 6 feet tall stands 17 feet from the base of a streetlight. If the person’s shadow is 8 feet, estimate the height of the streetlight.

We are being asked to find the height of a streetlight, this will be (x).

You can use similar proportions here to solve this quickly.

\( \frac{x}{6} = \frac{25}{8} \)

\( x = \frac{(6)(25)}{8} \)

\(\boxed{x = 18.75 ft.} \)

The streetlight is 18.75 feet tall.

Example 10

Pure water is being added to a 30% solution of 153 ml of hydrochloric acid. How much water should be added to reduce it to a 13% mixture?

We are asked to find the amount of water that should be added to 153ml of 30% acid to make it a 13% solution. Let this amount of water equal x. Then x + 153 equals the final volume of the 13% solution.

Since only water is added, the total amount of acid in the solution after adding the water must equal the amount of acid before the water is added. The volume of pure acid after the water is added equals 13% of x + 153ml, and the volume of pure acid before the water is added equals 30% of 153ml. Our equation becomes:

\( .13(x + 153) = .30(153) \)

\( x + 153 = \frac{.30(153)}{.13} \)

\( x = \frac{.30(153) -153}{.13} \)

\(\boxed{x = 200.08 ml} \)

Inequalities of the Linear Kind

An example of an inequality is: \( x^2 -1 < 10 \). In this way they are similar to linear functions. They can have any number of variables or exponents. Solving an inequality is finding the values for one or more variables that make the statement true. Inequalities can also be linear or nonlinear.

A solution to any particular linear inequality will often be written as an interval. These will be real numbers and not imaginary. Intervals can be open or closed. This depends on the values. A closed interval looks like \( [2,5] \). An open interval take this form: \( (3,9) \).

Inequalities can be solved in a few different ways. The main way is just like linear equations since they are similar. However, do realize that they can be solved using tables if they are in the correct form.

Example 1

\( 2x-3 < \frac{x+2}{-3} \)

The first step you do is multiply by -3 and then reverse the inequality sign.

Anytime you multiply or divide a negative number through an equation you will reverse the inequality sign.

\( -6x +9 > x + 2 \)

Now add 6x to both sides.

\(9 > 7x + 2\)

Subtract 2 from both sides now. Our goal is to have the same type of values on either side.

\(7 > 7x \)

Divide both sides by 7.

\(\boxed{1 > x} \)

Example 2

Solve: \(-3(4z-4) \geq 4 - (z - 1) \)

Distribute everything to make it easier.

\(-12z + 12 \geq 4 -z + 1 \)

Group everything as much as possible. This makes it easier to deal with and find a solution.

\( -12z +12 \geq -z + 5 \)

We should now group the terms together so we can better deal with them.

This means combining the <z> terms.

\( -11z + 12 \geq + 5 \)

Now we need to isolate the variable.

To do that, we subtract 12 from both sides.

\( -11z \geq -7 \)

the last thing to do is get rid of the coefficient in front of our variable.

\( \boxed{z \leq \frac{7}{11}} \)

Example 3

Solve: \( 1-x \geq \frac{1}{2}x -2 \)

Here we have an inequality with a fraction in it. It follows the same rules as other equations.

Let us first subtract one from each side, so we can isolate the variable.

\( -x \geq \frac{1}{2} x - 3 \)

Since we have <x> variables on each side of the equation, we need to get them all on one side.

We do this by subtracting the <x> that also has a constant on its side.

\( \frac{-3}{2}x \geq -3 \)

Our next step is to get rid of the coefficient in front of the <x>.

We do this by multiplying \( \frac{-3}{2} \) to each side of the equation.

Remember, any time we multiply or divide an inequality by a negative we also reverse the inequality sign.

\( \boxed{x \leq 2} \)

Example 4

Solve: \( -4 \leq 5x + 1 < 21 \)

This is a different type of inequality.

They are compound inequalities.

It means there are multiple inequalities in the same equation.

Let us see how to work with these.

\( -4 \leq 5x + 1 < 21 \)

Our first goal is to isolate the variable in the middle.

This means no constants with the variable.

Subtract 1 from each portion.

If there are two inequalities then you have three portions.

\( -5 \leq 5x < 20 \)

Now we isolate the variable so there is no longer a coefficient.

To do that, we divide by 5 because that is the coefficient of x.

\( \boxed{-1 \leq x < 4} \)

Example 5

Solve: \( 32 \leq 70 - 29x \leq 50 \)

This is another compound inequality.

We need to isolate the variable and the first step is to get rid of the constants.

Let’s start with subtracting 70 from each portion of the inequality.

You can subtract from each portion like this when you have a constant in each portion.

\( -38 \leq -29x \leq -20 \)

The next step is to get rid of the coefficient in front of our variable.

To do this, we divide all portions by <-29>.

Since we are multiplying or dividing by a negative, we will reverse each inequality.

\( \frac{-38}{-29} \geq x \geq \frac{-20}{-29} \)

We can simplify these terms now.

A negative divided by a negative is a positive, so let us rewrite these terms.

\( \frac{38}{29} \geq x \geq \frac{20}{29} \)

That looks nicer now that we have done that.

We can do more though.

Let’s also write it with the smallest number on the left.

We will reverse the signs again when we do this.

\( \boxed{\frac{20}{29} \leq x \leq \frac{38}{29}} \)

Example 6

Solve: \( \frac{-x}{2} + 1 \leq 3 \)

We want to isolate the variable.

To do this, we get rid of the constants first.

In this example we subtract <-1> from each term.

\( \frac{-x}{2} \leq 2 \)

Our next step is to get rid of the coefficient in front of the variable.

It may not be obvious, but it really \(\frac{-1}{2} * x \).

Since this is the case, we will multiply both terms by -2.

We are multiplying each term by a negative, this means we reverse the inequality.

\( \boxed{x \geq -4} \)

Example 7

\( -8 < \frac{3x-1}{2} \leq 5 \)

Here we have a more complicated looking example.

The middle term is a fraction and we will need to deal with it first.

To start, multiply each term by 2 since that is the denominator of the fraction with our variable.

\( -16 < 3x - 1 \leq 10 \)

That will be much easier to deal with.

Now we want to get rid of the constant in the term with our variable.

Add +1 to each term.

\( -15 < 3x \leq 11 \)

Now we want to get rid of the coefficient in front of our variable which is 3.

Divide all terms by 3.

\( \boxed{-5 < x \leq \frac{11}{3}} \)

Example 8

Solve: \( 5(x-6) < 2x - 2(1-x) \)

We need to get this problem in the correct form, so we need to distribute these terms first.

\( 5x - 30 < 2x -2 + 2x \)

Next, let us simplify a bit and combine terms so that it makes more sense.

In the second term, let us combine both variables together.

\( 5x - 30 < 4x - 2 \)

Let us simplify some more.

We should subtract 4x in the second term since it is the smaller of the two variables.

\( x - 30 < -2 \)

Now we should isolate the variable and add 30 to both sides.

\( \boxed{x < 28} \)

Piecewise Functions

Functions can model just about any kind of data. Real data can be problematic though. This brings us to a piecewise function in this chapter.

It is a function that has multiple parts that can't be represented by a single complete function. This means this type of function can be in several different pieces. The whole function itself is not linear but its separate pieces can be.

A function's input value its x-input. A piecewise function will behave differently depending on what that x-input is.

\[ f(x) = \begin{cases} 1 & \text{if $|x| \leq 1$} \\ 0 & \text{if $|x| > 1$} \end{cases}\]

A piecewise function is discontinuous. It is not a continuous function. In other words, it will be defined differently for each interval.

To solve these functions:

- See where the x-input is in the defined interval

- Then evaluate x with the given function.

Greatest Integer Function

The greatest integer function is a type of piecewise function.

\[ f(x) = [[x]] \]

\( [[x]] \) is the greatest integer less than or equal to x. It is a way of rounding to the kind of value that you want. It is rounding down, basically.

\[ [[5.5]] = 5 \]

\[ [[-3.5]] = -4 \]

See how that works? You are just rounding to the lower value that is an integer. That is the greatest integer function.

These functions are also divided into intervals. The intervals can be positive or negative. They are made up of real numbers, however. So no complex or imaginary numbers at this point.

This is also a type of discontinuous function. A graph of this function can look like steps. That is always your clue that it is discontinuous, the points do not connect in a logical way. The steps can either go up or go down.

Absolute Value Function

The absolute value function looks like a "v" shape on a graph. This makes it easy to identify. This function can also be defined as a piecewise function.

They are algebra expressions that contain absolute value symbols. These symbols look like \(f(x) = |x|\). The absolute value of this number will be its distance from 0 on the number line.

Equations will look like \( y = |ax + b| \). The bars denote the function is absolute or always positive.

These equations are always even with or above the x-axis. The vertex of the graph is the x-intercept. You can find this by solving for \(ax + b\).

Its domain is always real numbers but its range can be positive or negative. To shift this function vertically, the equation changes to look like \(f(x) = |x| + k\). This will make the vertex of the graph greater than zero.

Absolute Value Inequalities

Since these can be inequalities, the solution to an absolute value inequality will be an interval. This type of expression looks like \( |x| < 5 \). They are asking you to find all the x-values that are less than 5 units away from zero in either direction.

So, \( -5 < x < 5 \) is what this expression is telling you. This is a good example of a less than inequality.

There are also greater than inequalities. They are handled somewhat differently. In an inequality \( |x| > a \), you start by splitting this expression into two pieces. The pieces can be positive or negative, depending on the expression itself.

You can also see a problem that includes a negative x-value. There is no solution to this type of problem because an absolute value can never be negative.

Solving Quadratic Equations

In previous sections we discussed linear equations and functions. Let us now increase the difficulty ever so slightly to the famed quadratic equations and functions. A quadratic function will have an \(x^2\) in it.

Something like:

\[ x^2 + 2x -3 \]

The domain of a quadratic function is all real numbers. Its graph is a parabola. The parabola can open either up or down. A parabola opens upward if the leading coefficient is positive. Conversely, it opens downward if the leading coefficient is negative.

The highest or lowest point of a parabola curve is the vertex. A line passing through the vertex evenly is the axis of symmetry.

Leading coefficients of the quadratic function also control the width of the parabola. Large values make a parabola narrow while smaller values make the parabola wider.

Completing the Square

When a quadratic function is in the form \(ax^2 + bx + c\), you do not know where the vertex is. If you remember, the vertex is the lowest or highest point of the graph.

To know where the vertex is, the equation must be in a different form. It must look like \(a(x-h)^2 +k\). In this form, the vertex is located at the "h" and "k" positions. This is called the vertex form.

Vertex Formula

This formula will be very important hereafter. It is \(\frac{-b}{2a}\). It is key to different types of problems later on. It is also part of the very famous quadratic formula.

Example 1

Here is an example I found that should illustrate how this is done.

Convert the vertex form to the quadratic function form.

Change \(f(x) = 2(x-1)^2 +4\) to the quadratic form.

\[2(x-1)^2 + 4 = 2(x^2 - 2x +1) + 4\]

\[= 2x^2 - 4x +2 +4\]

Answer:

\[\boxed{= 2x^2 - 4x + 6}\]

We can change the form back the other way around too. Learning to do this is very useful. Depending on what you have to do, manipulating the formula to be in the correct form is essential. We do this by completing the square.

Example 2

Convert \(x^2 + 6x - 3\) to its vertex form.

We do this by completing the square.

\[f(x) = x^2 + 6x - 3\]

\[y + 3 = x^2 + 6x\]

So, in this equation, k=6. Add \(\frac{k}{2}^{2}\) to both sides.

\[y + 3 + 9 = x^2 + 6x + 9\]

\[y + 12 = (x + 3)^2\]

Answer:

\[\boxed{y = (x + 3)^2 - 12}\]

These types of problems have a nice practical side too. This next example is a classic word problem given by teachers everywhere. We will look at it and go step by step.

Example 3

A farmer is fencing a rectangular area using the straight portion of a river as one side of the rectangle. If the farmer had 2400 feet of fencing, find the dimensions of the rectangle that give the maximum area.

So what we know is that the two small sides plus the length equal 2400 feet.

\[A = L*W\]

\[Width + Width + Length = 2400\]

\[2W + L = 2400\]

\[L = 2400 - 2W\]

\[A = L*W\]

\[A = (2400 - 2w) * W\]

\[A = 2400W - 2W^2\]

\[A = -2W^2 + 2400W\]

Now we use the vertex formula to find our missing values.

Vertex formula is \(\frac{-b}{2a}\).

\[W = \frac{-2400}{(2)(-2)}\]

\[W = 600\]

We know from earlier what our length is.

\[L = 2400 - 2W\]

Now we just replace the value for \(W\).

\[L = 2400 - (2)(600)\]

\[\boxed{L = 1200}\]

So the dimensions for our rectangle are \(600 \text{by} 1200\).

There I are some things I learned when I first did this. Use your symbols as long as you can before you start entering values in. The reason why is that sometimes you can get off track by worrying about the values for this and that variable.

The other main thing I learned when attempting this was that the vertex formula just wants the coefficients. It does not need the variable or the value for that variable. That wasn't really clear to me at first.

Let us do another problem of a similar type.

Example 4

Here is another problem. A farmer has 1000 feet of fence to enclose a rectangular area. What dimensions for the rectangle result in the maximum area enclosed by the fence?

Unlike the last problem, this is a full rectangle. It has 4 sides instead of 3. We approach it the same way.

We know that \( 2L + 2W = 1000 \).

So a rectangle has 4 sides. Two of them can be called "L" and 2 can be called "W". That is where the formula comes from.

Our goal is to find both "L" and "W". From the original formula:

\[2L = 1000 - 2W\]

Divide both sides by 2.

\[ L = \frac{1000-2W}{2}\]

Simplify the right side.

\[ L = 500 - W \]

Remember that \( A = LW \). That means:

\[ A = (500 - W) (W) \]

Multiply those two expressions together.

\[ A = -W^2 + 500W \]

Now we use our vertex formula, \(\frac{-b}{2a}\).

\[\frac{-500}{(2)(-1)}\]

\[ \frac{-500}{-2} \]

\[ W = 250 \]

We just need "L" now but we figured out the formula for that earlier:

\[ L = 500 - W \]

Substitute in "W" now.

\[ L = 500 - 250 \]

This gives us:

\[ \boxed{L = 250} \]

This this gives us the dimensions "250 x 250".

The Motion Formula

The motion formula is very popular in both algebra and calculus. It looks like:

\[ s(t) = -16t^2 + v_0t + h_0 \]

There are multiple versions of this formula, depending on the units. This

version of the formula calculates the height of the object in feet after "t"

seconds.

The \(h_0\) portion of the formula denotes the initial height of the object.

\(v_0\) denotes the initial velocity above some reference point. If the initial

velocity is upward then \(v_0\) is greater than zero. However, if the initial

velocity is downward then \(v_0\) is less than zero.

Example 5

Here is a problem about the flight of a baseball.

The initial velocity is 80 feet per second.

Initial height after it leaves the bat is 3 feet.

How high is the baseball after 2 seconds?

Lastly, find the maximum height of the baseball.

Remember our motion formula:

\[ s(t) = -16t^2 + v_0t + h_0 \]

The problem gives us all the values in a straightforward manner.

We can just substitute them directly into the formula.

Our formula now looks like this:

\[ s(t) = -16t^2 + 80t + 3 \]

This is our basic formula with the information we are given.

Now lets think about what the problem asks.

How high is the baseball after 2 seconds?

So, we already have a time variable in the formula just waiting to be used.

We just plug it in there and do the calculation.

\[ s(2) = -16(4) + 160 + 3 \]

\[ s(2) = 99 \]

So our baseball attains a high of 99 feet after two seconds.

The next questions is to find the max height of the baseball.

Our "a" coefficient is negative so that means the parabola opens downward.

The vertex will be the highest point on the graph.

\[ t = -\frac{b}{2a} \]

\[ t = -\frac{80}{-32} \]

\[ t = 2.5 \]

That gives us the x-coordinate.

We put that back into the formula just like we did before.

\[ s(2.5) = -16(2.5)^2 + 80(2.5) + 3 \]

\[ \boxed{s(2.5) = 103} \]

The max height of the baseball reached 103 feet and it took 2.5 seconds to get there.

Thinking about motion in this manner is pretty interesting!

Let's do some examples for practice now to cement our knowledge.

Example 6

Is this expression linear or quadratic?

\[f(x) = 1-2x + 3x^2\]

It needs to be written in the proper form.

\[\boxed{f(x) = 3x^2 -2x +1} \]

This will be a quadratic function.

Example 7

Is this expression linear or quadratic?

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{x^2-1}\]

This expression looks weird right and is nothing like our examples before.

This expression is therefore neither linear or quadratic.

Example 8

Is this expression linear or quadratic?

\[\frac{1}{2} - \frac{3}{10} x \]

Despite being in a fractional form, this does not have an \(x^2\) term in it.

That will make this a linear expression.

Example 9

Is this expression linear or quadratic?

\[f(x) = -3x^2 + 9\]

This does not have an "x" term but it is no less a quadratic expression.

Conclusion

In this chapter we have covered quadratic functions and equations. Along with

quadratic functions come the parabolas. Parabolas are the graphing equivalent

of a quadratic function. If the coefficient of a quadratic function is

positive then the corresponding parabola will open upward. Conversely, if

the quadratic function is negative then its parabola will open downward.

We also covered the vertex of the parabola including how to find it. The

vertex formula \(-\frac{b}{2a}, f\frac{-b}{2a}\) is very important and will

remain so later on.

Factoring Quadratics

In the last section, I talked about the basics of quadratic equations. Now it is time to learn more about their characteristics. A quadratic equation takes the form of \(ax^2 + bx + c = 0\).

Quadratics can be solved symbolically. This should be no surprise. There are several techniques for solving them too. These include factoring, square root property, quadratic formula, and completing the square. We will start by learning to factor.

Factoring relies on the fact that if \(a*b = 0\) then either \(a = 0\) or \(b = 0\). Let us solve some problems to see how this works. I am working problems out of a textbook but I will try to explain the steps to the best of my ability.

Problem 1

Solve: \(2x^2 + 2x - 11 = 1 \)

The first thing to do is to move everything to the left side of the equals sign so the equation will equal zero.

\[2x^2 + 2x - 12 = 0\]

You almost always want to get rid of any coefficients. In this problem 2 is the coefficient. To get rid of it, we just divide the whole left side by 2. This gives us:

\[x^2 + x - 6 = 0\]

Now it is time to factor. What I mean by this is that I am trying to find two numbers that will add to be the same coefficient as the <b> term and multiply to be the same coefficient as the <c> term.

I usually find it easier to start with the <c> term and find multiples of that coefficient. The coefficient of the <c> term -6. So we are looking for two numbers that you can multiply together to get -6 and add to +1. It looks like 3 and -2 will work.

\[x + 3 = 0\]

\[x -2 = 0\]

\[x = -3\]

\[\boxed{x = 2}\]

So for this equation <x> can equal -3 or 2.

Problem 2

Solve: \(12t^2 = t + 1\)

We immediately see that the equation needs to be rewritten. Everything needs to be on one side and we need to get rid of the coefficient. Let’s rewrite it first.

\[12t^2 -t -1 = 0\]

This is a more difficult factoring problem. I’ll get you through this, though. First, keep in mind that our factors are correct when we can multiply them back together and get the original equation. That is how you check to see if you are right.

So we already know that this equation is different. It is different in the manner that we need all the factors of <-1>. We also have to have two numbers that multiply to 12 so we get the correct coefficient. Let’s start with something and see what happens.

\[(4t + )(3t - )\]

Our <c> term is negative, so we know one of our two factors will also be negative. Our two factors of -1 will be +1 and -1. So we will randomly try those in the above factors.

\[(4t +1)(3t -1) = 0\]

We multiply that back out to see if it gives us our original equation. It does. So that means I got lucky as it could have been the other way around. When you multiply your factors back together, you will often get the wrong equation that what you had originally. This means you need to try different factors of your <c> term or just change the position.

\[4t = -1\]

\[3t = 1\]

So:

\[t = \frac{-1}{4}\]

or

\[\boxed{t = \frac{1}{3}}\]

Problem 3

Solve: \(24x^2 +7x -6 =0\)

This is a crazy-looking equation! However, let’s take it one step at a time. This is key to most things in math, physics, and programming by the way. You want to break down enormous problems into smaller ones as much as possible. It starts here.

So when I look at this I know I need factors of 24 and factors of -6. There are several factors of 24 such as 1, 24, 2, 12, 3, 8 that include negative versions of those listed.. Factors of 6 include 1, 6 2, 3 and more negative versions.

I won’t make you read all my poor attempts but it took me several minutes of trying combinations and then multiplying them back out to find the original equation. However, trial and error like that is just what has to be done sometimes. I finally got the correct pairs.

\[(3x +2)(8x -3) = 0\]

\[3x +2 = 0\]

and

\[8x -3 =0\]

That gives:

\[ x = -\frac{2}{3}\]

and

\[\boxed{x = \frac{3}{8}}\]

These factors that we have been finding of these equations are actually the x-intercepts of equations. That is important to remember.

Conclusion

In this chapter, we looked at solving quadratic equations by factoring. This is an important technique for algebra and beyond. I did a few problems here but if you feel you need more practice, then any algebra textbook should have problems to practice with.

Algebraic Functions

Functions are a type of relation that tie numbers together. They have to have a mutual meaning, but when they do, the data given can be very meaningful.

Beginning functions often use tables for a visual aid. Tables in this fashion show the direct relationship between a set of numbers.

A function is a relation. It is defined as an input that has only one output. In an ordered pair, like (2,3), the first number corresponds to the (x) and the second number corresponds to the (y).

Notation and Pairs

When talking about functions, the notation y = f(x) is traditionally used. This means that when (x) is used as an input into (f), then the result is y. That is a fundamental relationship and must be understood.

It is important to realize that a function returns a set of ordered pairs, like (x,y). A relation that has one output for each input is, by definition, a function. (x) is the independent variable and (y) is the dependent variable.

A set of inputs (x) is called the domain of the function. The set of related outputs (y) is the range of the function. A letter (f) is usually the name of a function.

A function can be represented in words, a table, or a diagram. They all mean the same thing. Each method will have its limitations.

For notation, we use both brackets and a parenthesis. These mean different things in interval notation. When we use a bracket it means the endpoint number is included. The parenthesis is used when the endpoint number is not included.

Definition Of Functions

Functions can be represented verbally, graphically, symbolically, or numerically. There is no best way, it depends on the situation and the data you want to show.

Every function is a relation but not every relation is a function. This is important to remember. The domain is the set of all real numbers for which it is defined.

When looking at a graph, we can see if a curve is a function or not. This is accomplished by the vertical line test. Any vertical line on the graph should only touch the curve once. If, for some reason, it touches more than once, then this is not a function.

Solving Functions

When you are asked to solve a function, it can also be called evaluating it. This is the same thing and its just a different way of phrasing it.

When we are given an input value, we are solving for the output value. Conversely, if we are given the output value, we set the equation equal to the output value and solve for the input.

Constant Functions

I want to add some detail to our definition of functions. They can be considered in another light, that is, they can be linear or nonlinear. An example of a linear function is called a constant function.

It should not be too hard to surmise what this is. A constant function is one who’s output remains constant. These are actually very common.

Linear Functions

This is a type of function where the output has the same rate of increasing or decreasing. It is represented by \(f(x) = ax + b\).

If a=0 at any point then we will just have a constant function. So in a linear function, each time x increases, f(x) changes by the amount of a.

Slope Of A Function

The graph of a linear function is a straight line. Slope is the number that indicates the inclination of this line. If you have two points, slope = m = \(\frac{\delta y}{\delta x}\).

If this slope is positive, it rises from left to the right. However, if its negative, the line sinks from left to right.

Example 1

Find the slope of the line passing through the points (-2,3) and (1, -2).

You calculate it like this:

\( m = \frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1} = \frac{-2-3}{1-(-2)} =\boxed{ \frac{-5}{3}} \)

Slope like this is also known as rate of change of a function. It is also a constant function.

When using a graph to figure out estimates, the units will be easy and given for you. It will be the units for the y-axis over the x-axis. Take advantage of this.

Nonlinear Functions

Nonlinear functions are easy to explain. They are functions with variable output. So the output does not increase or decrease with any regular interval. If you were looking at a graph, the line would be curved. This is what a curved line means.

If you are looking at a table of data and wonder if it is linear or nonlinear, just examine the output. That part should be labeled clearly. The output will have the same rate of change if it is linear, otherwise it is nonlinear.

An example of a nonlinear function would be a parabola. This is a curved line, which can take a variety of shapes.

Finding Domain And Range

We can also use graphs to find information about a function. Graphs give us a broad overview of functions. There will be many inputs so we can see what the function is all about.

Like any function, we can see the domain as the (x) inputs and the range (y) outputs. This is an easy way to see if the graph is a one to one function. That means there is only one output for any input. It's just another style of function.

Average Rate of Change

Since the graphs of nonlinear functions are not straight, there is no single slope. Instead, there are many different slopes in a particular curve. However, we can take an average of the slopes to get a general idea. This is an important calculus topic too.

If we have two points on a curve and draw a straight line connecting them, we call this a secant line. So the average rate of change is telling us, on average, how fast a quantity is changing. The average rate of change is just the slope of that particular line between two points.

When a function is constant, its average rate of change, or slope, is 0. In a linear function such as:

\( f(x) = ax + b \)

its average rate of change is equal to a, the slope of its graph. A nonlinear function has a variable rate of change.

Just so you know, we can define out two points to anything we want. For example, it can be from start to finish or some small instance between the two ending points.

This looks like:

\[\frac{y_2-y_1}{x_2-x_1}\]

or

\[\frac{\delta y}{\delta x}\]

Example 2

Calculating A Difference Quotient

If \( f(x) = x^2 - 2x \) Find \(f(x+h)\)

Our expression is \( x^2 - 2x \) . We substitute \((x+h)\) for every \((x)\) in our expression.

\( f(x + h) = (x + h)^2 - 2(x + h) \)

Now multiple the expression out.

\( f(x + h) = x^2 + 2xh + h^2 -2x -2h \)

Ok that gives us \( f(x + h) \) . Now we input that into our difference quotient.

\( \frac{ f(x + h) - f(x)}{h } = \frac{ x^2 + 2xh + h^2 -2x -2h- (x^2 - 2x) } {h} \)

Lets rewrite that ending part so everything has the correct sign.

\( \frac{ f(x + h) - f(x) } {h} = \frac{ x^2 + 2xh + h^2 -2x -2h -x^2 + 2x } {h} \)

It should be immediately obvious that a few things will cancel out. Lets do that.

\( \frac{ 2xh + h^2 -2h }{h} \)

\( \frac{ h(2x + h -2) } {h} \)

\( \boxed{2x + h -2} \)

This is our answer. These problems are usually designed so they cancel out certain values to make it work. So when working these, if the problem does not behave like that, you might have made a mistake and need to go back and look at it.

Example 3

The distance in feet that a racehorse travels is given by the function

\( d(t) = 2t^2 \)

Find \(d(t + h)\)

Find the difference quotient.

We will be substituting \((t+h)\) for t in the expression \(2t ^2\)

\( d(t+h) = 2(t+h)^2 \)

\( 2(t^2 +2th + h^2) \)

This gives us \((2(t+h)\)

\( = 2t^2 + 4th + 2h^2 \)

Now lets calculate the difference quotient.

\( \frac{d(t+h) - d(t)}{h} = \frac{2t^2 + 4th + 2h^2 -2t^2}{h} \)

Cancel stuff out and rewrite it.

\( \frac{4th + 2h^2}{h} = \frac{h(4t + 2h)}{h} \)

Cancel those h’s. We get:

\( 4t + 2h \)

If t=7 and h=.01, then the difference quotient becomes:

\( 4t + 2h = 4(7) + 2(.1) =\boxed{ 28.2} \)

Increasing And Decreasing Functions

Graphs tell us a lot about a function. We can look at the function as a whole or any particular intervals that interest us.

Another attribute the graph tells us is whether the function is increasing or decreasing. An increasing function means the slope is positive. A decreasing function is when the slope is negative.

The function can be looked at as a whole or at any point in time on the graph. This gives us a lot of information, depending on the function.

A point on the graph that goes from increasing to decreasing is called a local maximum. If a point goes from decreasing to increasing, then that point is called the local minimum.

Conclusion

So functions are very interesting. They can tell us a nice picture on what each one means. Constant and linear functions are easy to understand but its also important to remember what they represent and how they look graphically.

The slope on a graph is the degree of the rise and fall of a line between two points. This is also the rate of change. Rate of change tells us how fast any quantity changes. This then leads us to difference quotients.

Transforming Graphs

We can shift functions in many ways on a graph. This is important to understand so you can accurately model a function when you need to. They can be shifted left, right, up, down, and even stretched.

- f(x) + c =graph is shifted upwards

- f(x) - c =graph is shifted downwards

- f(x + c) =graph is shifted to the left

- f(x - c) =graph is shifted to the right

- -f(x) =graph is reflected across the "x" axis

Shifting Up And Down

Say you have a function:

\[f(x) = x^2\]

This is your typical parabola. In this form its vertex is at (0,0).

When we shift it, we are moving the whole curve in some direction.

When we want to shift it upward, we can rewrite the equation as:

\[f(x) = x^2 + 3\]

Here is the graph that shows the function shifted upward by 3 units above the “x” axis. You can see the vertex and whole curve is shifted upwards by 3 units. That is what the constant does in the equation above.

It works the same way when you want to shift it downward.

\[f(x) = x^2 - 3\]

As you can see, the vertex is 3 units below the “x” axis now.

These movements of the function are called horizontal and vertical shifts. They just adjust the position of the function on the graph.

In fact, we can build the graph from the function. This is helpful when we want to graph an equation to better understand it. That is an important idea later in mathematics.

Shifting Left And Right

You can also adjust the position of a function left or right of the “y” axis. We accomplish this by modifying the variable of the function.

\[f(x) = (x-3)^2\]

This will shift the function to the right of the “y” axis by 3 units. So far, everything is still on the "x" axis, but we can change that too.

You can do the same process to shift the function to the left.

\[f(x) = (x+3)^2\]

We know these as horizontal shifts. They can be combined with any other type of transformation.

Combining Shifting Methods

Combining the methods that we have already discussed is very useful. Let’s shift this function up and left on the graph.

\[f(x) = (x+3)^2 + 3\]

Here is the corresponding graph.

The constant moves the graph upward 3 units, while the "x" variable is modified by +3 in order to move the graph left by 3 units.

We can do the opposite and shift the function downward and to the right.

\[f(x) = (x-3)^2 -3\]

Here is the graph for that combination of shifting. The is kind of the opposite of the previous example. The constant (-3) moves the graph downward by 3 units. Then the "x" variable is again modified by the (-3) in order to move the graph to the right.

Stretching A Function

We can manipulate functions in a variety of ways. Stretching a function is another way. This done by adding a coefficient in front of the function. Behavior is a little less intuitive. The reason why is that it depends on the function itself.

Playing with the coefficient in front of the function will stretch a function along the “y” or “x” axis. It depends on the coefficient. Generally, a positive coefficient will stretch a function along the “y” axis. Conversely, a coefficient less than 1 will stretch it along the “x” axis. You should experiment with your graphing software to see how the main functions are affected.

\[f(x) = x^3\]

This is our typical cubic function. Now let us add coefficients in front of it to see what happens.

\[f(x) = 10x^3\]

See how it gets narrower? It is being stretched along the “y” axis. It is thinner overall and hugs the "y" axis even closer than before. Now let’s do another.

\[f(x) = \frac{1}{10}x^3\]

This example widens our function a lot. It is being stretched along the ‘x” axis. This is because of the coefficient that is less than 1. The small the coefficient, the wider this graph gets.

Reflection Of Graphs

Reflecting graphs can also be done. We accomplish it by applying a negative to the original function.

When you reflect across the “x” axis, it is -f(x). Whatever is inside this function will have the opposite sign and value. This is how everything gets translated across perfectly

We can take our function:

\[f(x) = x^3\]

Then, to reflect it across the “x” axis, we would apply a negative to the function as a whole.

\[-f(x) = -(x^3)\]

We can see what is happening here because it is the opposite of the regular graph.

Conclusion

In this article, we have talked about the transformation of graphs. Basic transformations include shifting upward, downward, left, and right. We can also stretch a graph along the “x” and “y” axes.

We also talked about stretching and reflecting graphs. These are all important, and together, let us build a graph from equations.

Nonlinear Functions

We have already talked about linear functions, where growth rates are the same. So, when growth rates change, we call this nonlinear growth. Nonlinear growth happens in many situations. Two ways in which we can see nonlinear growth are in quadratic and exponential functions. We have already talked about quadratic functions, so this should not be surprising.

Polynomials

Polynomial functions are useful, especially in graph form. In graph form, it is easy to see how a function be haves and what it means. Polynomials deal with real numbers and its graph will be continuous. We can describe them by their characteristics:

- Formulas

- Degrees

- Coefficients

When looking at the formula, we can see a lot about the function. The degree of a polynomial is directly related to the variable exponent, like x^2 or x^3. An x^2 function is a degree 2, for example. Coefficients change function behaviors in strange and interesting ways. I will get to that later.

Functions that are degree two or higher are nonlinear. Hopefully, you can start seeing the relationships between these different functions. I should also point out that any function with a radical, ratio, or absolute value is not a polynomial.

Is this a polynomial:

\[f(x) = 2x^3 -x +5 \]

Yes this is a polynomial because it does not contain radicals or complex numbers.

Is this one a polynomial:

\[f(x) = \sqrt{x} \]

This one is not a polynomial because it contains a root.

Increasing and Decreasing Functions

When looking at a graph of a function, it can stay constant, increase, or decrease. You already know what a constant function is. So, a function that is increasing is going uphill from left to right. Conversely, a function that goes downhill, from left to right, is a decreasing function.

We can also look at a function over a certain interval. It can be the entire interval of a function or just a small piece of it. For example, if we had a report on the revenue of a company over several years, we could evaluate the profits for certain years. This would look at a small interval of a function to see if it was increasing or decreasing.

Is this function increasing or decreasing?

\[f(x) = -3 \]

This function is neither increasing or decreasing.

Is this function increasing or decreasing?

\[f(x) = 2x - 1 \]

This function is increasing and it never decreases.

Symmetry in Functions

Symmetry in functions is an important topic later on. For now, it can tell you whether or not a function is even. A function is symmetrical if it is the same on either side of an axis. We can see symmetry in nature and we often think of things that are symmetrical as beautiful. The same is true in math. We look for it because it tells us attributes about a function.

A function is even if it is symmetrical around the y-axis. The function is odd if it is symmetrical around the x-axis. We can also tell this by looking at the equations themselves. If a function only has even exponents, it is an even function. This means that a function that contains only odd exponents is an odd function.

Another important fact is that many functions and their graphs have no symmetry at all. This is completely normal, so you should expect it.

Nonlinear functions can increase or decrease when represented graphically. This can change depending on the interval. For example, a function can be both increasing or decreasing, depending on the interval. When these functions are degree two or higher, they are then nonlinear.

Is this function even, odd, or neither?

\[f(x) = 5x \]

This is an odd function.

Is this function even, odd, or neither?

\[f(x) = x + 3 \]

This function is neither even or odd.

Is this function even, odd, or neither?

\[f(x) = x^2 - 10 \]

This would be an even function.

Polynomial Functions

Historically, these have greatly interested mathematicians. The reason why is that they are very useful in modeling data. We use them all the time for this. Computer science, mathematics, data science, and several other disciplines use them regularly.

Polynomials in graphs are continuous. Their lines have no breaks. Since they include only real numbers, radicals and complex numbers disqualify them. Their coefficients must also be real numbers.

We can break down polynomials. Different forms of a polynomial mean different things.

- function —— f(x) = x^2 + 2x + 2

- polynomial——x^2 + 2x + 2

- equation——x^2 + 2x + 2 =0

It will be important to know these differences.

Another important definition, a turning point, is when a graph changes from decreasing to increasing. A turning point is defined as the point in which this happens.

As you know, polynomial functions can have many different levels of exponents. The exponents mean a lot, graphically. A function with an x^3 term will have three intercepts and 2 turning points. An x^7 function will have 7 intercepts and 6 turning points. So, you can look at a function and tell a lot about it. A parabola crosses the x-axis twice, so it has an x^2 term, which we already know.

What is the degree and leading coefficient of:

\[f(x) = -2x + 3 \]

The degree is 1 and the leading coefficient is -2.

What is the degree and leading coefficient of:

\[f(x) = x^2 + 4x\]

The degree is 2 and the leading coefficient is 1.

What is the degree and leading coefficient of:

\[f(x) = -2x^3 \]

The degree is 3 and the leading coefficient is -2.

Piecewise Polynomials

You can have piecewise polynomial functions. In order for this to happen, each separate part of the function has to be a polynomial. You treat each part as a separate part unless asked to do something unique.

Conclusion

Polynomial functions that are at least second degree have more complicated graphs than a constant function. You can tell the x-intercepts and turning points from the shape of a graph. This makes the study of graphs beneficial. As previously stated, nonlinear and polynomials have a continuous graph. They also are made of real numbers and have real number coefficients.

Why We Factor Polynomials

We already know how to work with quadratic equations. That subject was covered previously. We saw that once factored, we could analyze their “zeros” and see where the equations were equal to zero. This gives us valuable information.

The curves equal zero where the lines intercepted or crossed the x-axis. This will give us the factors of the equation that we need.

The problem is, what if they give us an equation that is not nice and neat?

For example, some polynomial that is not a quadratic and needs work done to it in order for us to solve it. This is where division of a polynomial can be handy.

Sometimes, we can see on a graph where a curve equals zero at one place but it is not clear at other points. This is why we need to divide that single point out of the existing polynomial so we can analyze the rest of it.

Let’s start with some easy examples:

Example 1

\[ \frac{3x^4-2x^2-1}{3x^3} \]

The denominator is a monomial, and we are dividing each term by the denominator.

\[ \frac{3x^4}{3x^3} \longrightarrow x \]

\[ \frac{-2x^2}{3x^3} \longrightarrow \frac{-2}{3x} \]

\[ \frac{-1}{3x^3} \longrightarrow \frac{-1}{3x^3} \]

We now put all those terms together to get:

\[ \boxed{x - \frac{2}{3x} - \frac{-1}{3x^3}} \]

Example 2

\[ \frac{5x^4-15}{10x} \]

As before, we divide each term into the numerator by the single term in the denominator.

\[ \frac{5x^4}{10x} \longrightarrow \frac{1}{2x^3} \]

We do the same for the last term in the numerator.

\[ \boxed{\frac{-15}{10x} \longrightarrow \frac{-3}{2X}} \]

Example 3

\[ \frac{6x^3-3x^2+2}{2x^2} \]

Again, we have a single monomial in the denominator.

We divide each term into the numerator by the denominator.

\[ \frac{6x^2}{2x^2} \longrightarrow 3x \]

Now, we do the same for the second term.

\[ \frac{3x^2}{2x^2} \longrightarrow \frac{-3}{2} \]

Once more, we go to the last term.

\[ \boxed{\frac{2}{2x^2} \longrightarrow \frac{1}{x^2}} \]

Division Remainders

When doing division upon polynomials, you will often end up with a remainder.

It may not be intuitive, but there is a rule for this. When doing division, the remainder is set over the original term we are dividing by.

Let’s use the previous problem as an example again.

\[ \frac{6x^3-3x^2+2}{2x^2} \]

If we ended up with a remainder in the above problem, say 3, it would look like this:

\[ \boxed{\frac{3}{2x^2}} \]

That would be the last part of our answer. Of course, we did not have a remainder in the last example, but that happens when you encounter them.

Example 4

Our function is:

\[ f(x) = 5x^2 -3x +1 \]

Divide this by :

\[ x-1 \]

and say what the remainder is.

We start out by dividing the first term by x-1.

\[ \frac{5x^2}{x} = 5x \]

Now we multiply by “x” and “-1”. Don’t forget to change the sign.

We do addition on “-3x” and “5x”. Then we divide “2x” by “x”.

\[ \boxed{\frac{2x}{x} = 2} \]

We multiply through again and get a remainder of 3 which is the correct answer.

Factoring Polynomials

At the beginning of this section, I declared why we factor equations. Remember, factoring gives us information we need about an equation. The factors give us the “zeroes” of that equation’s curve. The “zeroes” are where the curve intercepts the x-axis.

A polynomial has a factor if the factor equals 0. This is always how we can check our work. Substitute that factor back into the equation. If the equation turns out to be 0, then we do indeed have a factor.

With all of this information, we can give a complete factored form. A complete factored form involves the function, any coefficients, and the factors. If you do not know the factors, determine those first.

We can give you a graph or just the function. We can model the algebraic function using software or a graphing calculator. This is usually acceptable or even preferred. Once you have the function graphed, you can see the “zeroes” on the graph. Use the coefficient information that you have to give the complete factored form.

Example 5

Write the complete factored form of:

\[ f(x) = 2x^2 - 25x + 77 \]

The zeros are:

\[ \frac{11}{2} \text{and} 7 \]

Our coefficient is 2, and they gave us the zeros. This gives us:

\[ \boxed{2(x-\frac{11}{2})(x-7)} \]

Graphs and Factors

If you haven’t noticed, polynomials can have even or odd levels of exponents. Polynomials behave differently in graphs depending on this multiplicity. An even multiplicity is 0,2,4 and so on. Odd multiplicities are 1,3,5.

The odd multiplicities cross the x-axis at its zero point. Even multiplicities just intercept, or touch the x-axis at its zero point. I’m sure you have seen graphs that exhibit this behavior, and this is why.

Rational Zeros

This is an interesting little test. It isn’t always applicable, but it can be useful. If a polynomial has a zero that is also a rational number, then you can use the rational zero test with it.

First, write out the factors of your coefficient and constant terms. It is easier to write them on separate lines or in a table so we can compare easily them.

When you can see them easily, make a list of all combinations of factors. Substitute these factors into the original equation and evaluate the function. Any of them that makes the function equal zero are a real factor. A second degree polynomial will have two factors and a third degree polynomial will have three factors.

Solving Polynomials

Factoring and using the quadratic equation are the two principal methods of solving polynomials. The problem with the quadratic equation is the polynomial needs to be in quadratic form. If it isn’t, you need to see if you can get it there.

This is where we go back to our factoring tool. If you have a cubic or greater function, then you can factor an “x” or more out of it to get it into quadratic form. This concept will continue to be important from here on out.

Example 6

Solve and find the (x) values.

\[ x^3 + x^2 - 6x = 0 \]

Start by factoring an (x) out of the equation.

\[ (x)(x^2 + x - 6 = 0) \]

This is a cubic function so we will have three (x) values.

We now factor the quadratic portion. We can see the factors of this equation.

\[ (x)(x-2)(x+3) = 0 \]

So, our answers are:

\[\boxed{ x= 0,2,-3} \]

Summary

When doing division with a monomial, divide the denominator into every term in the numerator. Polynomial division is like long division. The remainder theorem is when f(x) is divided by “x-a”, so the remainder is f(a).

The factor theorem, (x-a), is only a factor if f(a) - 0. When you have a zero with odd multiplicity, the graph crosses the x-axis at this zero. Conversely, when you have a zero with even multiplicity, the graph intercepts but does not cross the x-axis.

Hopefully, I have made it clear why we factor polynomials. We factor them to find the points that make the equation equal zero. These are factors and they are points where a graph will cross or intercept the x-axis.

We then discussed the tools that we used to factor polynomials. These include division, regular factoring, and the quadratic equation.

Fundamental Theorem Of Algebra

Until this point, we have tried several ways to solve equations. You may have noticed there are some types that we can’t solve by using the previous methods. These equations do not have real zeros, their graphs do not cross the x-axis at any point.

That is why they are difficult to deal with. We end up with negative values for solutions. For practical answers, what does a negative value mean? It does not mean a lot. Therefore, we have the concept of complex numbers.

Complex numbers were invented by mathematicians a long time ago in order to deal with these situations. They allow us to deal with a negative quantity in a way that makes sense. People are most familiar with this concept as the imaginary number, “i”.

Complex Numbers

When a graph does not have any x-intercepts, it does not have any actual solutions. When a graph does not have any proper solutions, we have to use the imaginary number to make sense of it. So, we can look at complex numbers in a couple of different ways.

\[i = \sqrt{-1}\]

\[i^2 = -1\]

This means we can rewrite solutions as complex numbers. Previously, we would not have a solution. However, with complex numbers now defined, we have solutions that make sense.

We usually write complex numbers in standard form, (a + bi). The (a) part is the real number, while the (bi) is the imaginary number.